Although co-design and participatory design are often used interchangeably, they are two different approaches to designing products and services. A recent paper on Co-production with Autistic adults 3 communicates the differences using a tiered diagram to indicate the levels in which participants are involved.

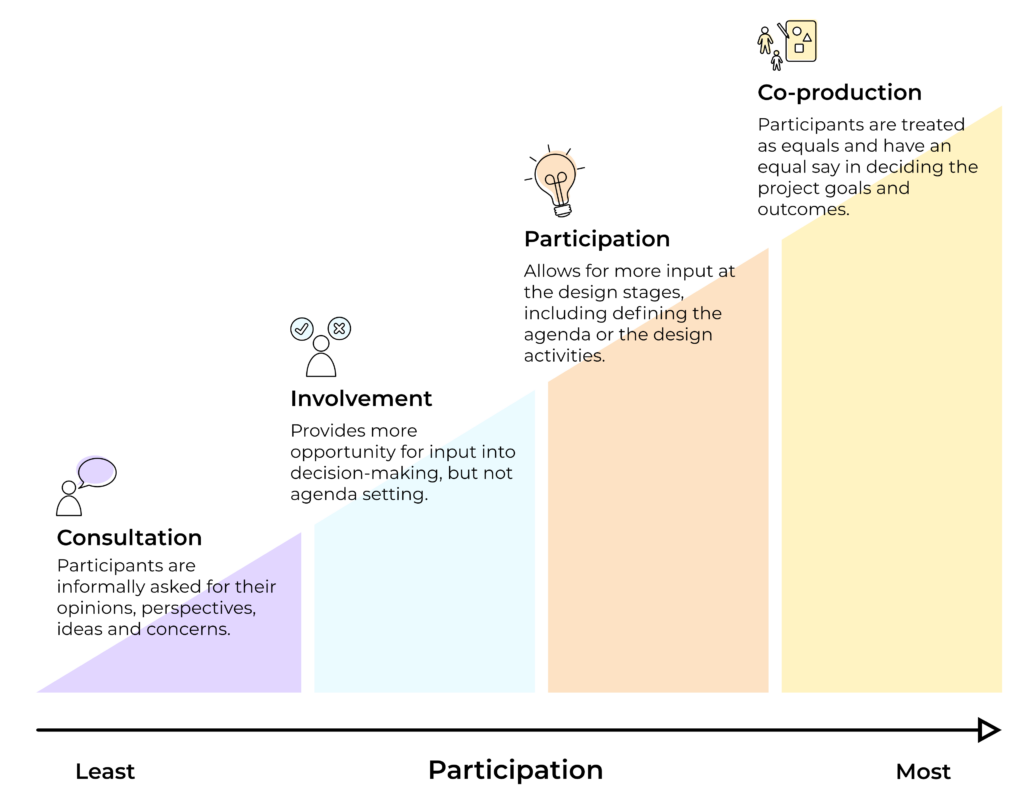

Figure 1, Passio’s adapted version of the tiered diagram, shows the different approaches to participant input; with ‘consultation’ involving the least amount of participation, and ‘co-production’ involving the most. In ascending order the tiers are:

- Consultation participants are informally asked for their opinions, perspectives, ideas and concerns.

- Involvement provides more opportunity for input into decision-making, but not agenda setting.

- Participation allows for more input at the design stages, including defining the agenda or the design activities.

- Co-production, participants are treated as equals and have an equal say in deciding the project goals and outcomes.

Why is the differentiation between co-design and participatory design important?

Participatory design is not inherently bad design. It is fantastic if you are asking for user-feedback! But we must be aware that the ‘locus of control’, that is, the decision-making power, ultimately rests outside of users and this has inherent risks of ability bias and if not handled correctly it could be viewed as Tokenism.

Ability bias is our tendency to design based on our own abilities, and thus, we might bias the feedback we are given. For example, we might prioritise a particular feature for development that users would not. Of course, there are often tradeoffs if some features are highly regarded by users but have high costs, but users are not stupid and will understand if it is communicated.

Tokenism is the act of appearing inclusive rather than being inclusive. I have spoken to users who refuse to take part in “co-design” for public bodies because they feel their voice is never listened to. The public body may have very good intentions and be making decisions on an economic basis, but we cannot dismiss how marginalised groups feel.

Sue Fletcher-Watson is a researcher that champions co-design. Like many researchers, she would “get research input into research” only once she had won grants. She changed this process to get input at the grant-writing stage to ensure the community was shaping research. She then went one step further by seeking an autistic mentor to aid in shaping research direction.

What should I use if I am building technology?

In the development process, participatory design entails acquiring feedback as the product is being built and incorporating the feedback into your tool. Getting feedback from users reduces the risk of building the wrong thing and is used in agile design.

However, co-design involves users at the start of the project and a different mindset of building a product together. It requires understanding, building relationships with users at the start, learning how they think and opening doors to finding novel and innovative solutions. But it also requires teaching skills to users so they can be involved in the process which can increase initial costs. Whilst it offers the greatest opportunity and reduces the risks of designing the wrong solution from the outset, it requires a great deal of practice to ensure that the process is effective whilst costs do not become a barrier to inclusion.